Let's start with the second question first. The "hardcore libertarian" position on drugs is that of full legalization of all drugs. This position is often contrasted with criminalization, although there are gray areas in which certain degrees of regulation exist. The "hardcore libertarian" position argues that problems associated with drugs will not go away, regardless of legalization or criminalization. The "hardcore libertarian" position posits that while legalization of drugs will harm certain lives, the harm caused by legalization is nowhere near the cost of criminalization or excessive regulation.

From 1919 to 1933, alcohol was prohibited in the United States. The Prohibition led to underground markets, powerful criminals, and increased crime. It was such a stupid move that we have a constitutional amendment reversing that poor life choice. A similar argument can be made about marijuana. It is true that there are individuals who struggle with marijuana addiction, and it is also true that marijuana can cause harm. At the same time, the costs of marijuana prohibition and enforcing marijuana laws decidedly exceed the costs of legalization. Looking at the evidence, it is clear that prohibition of alcohol was a bad idea, and that marijuana prohibition is a bad idea. The evidence for alcohol and marijuana legalization are relatively cut and dry. I cannot say the same for the opioid epidemic, and I am not the only libertarian who is doubting a strictly "free-market" drug market for opioids.

Opioids are some of the world's oldest drugs, so it's not as if opioids are a new phenomenon. The United States as a country has struggled with opioids since the Civil War. Civil War veterans needed pain relief. The solution? Morphine. In the early 20th century, they were being used as general pain management until the 1920s when doctors became aware of its addictiveness. Opioid usage reemerged in WWII to help veterans cope with pain. In the 1970s, drug use was becoming a huge problem, so the DEA greatly limited opioid usage. Doctors were hesitant to prescribe opioids until greater medical consensus developed in the 1980s and 1990s that it was not that harmful. The release of Oxycontin in 1996, as well as its subsequent success, helped boost prescription opioid consumption (see Pain and Policy Studies Group 1985-2015 consumption data of by opioid type here; Oxycodone numbers provided below).

Here is where the problem gets more complicated. Yes, there are thousands of opioid-induced deaths in the United States. There are thousands upon thousands of Americans who legitimately need pain relief. According to the National Institutes of Health, 11.2 percent (or 25 million) of Americans have daily pain, while 23 million suffer from a lot of pain. The American Pain Association estimates that as much as 50 million Americans have chronic pain. The response of using opioids as pain management was to a legitimate problem. Evidence also gets complicated in that opioids seem to do a better job at acute pain relief than chronic pain relief (Chou et al., 2015; Chaparro et al., 2014).

Let's complicate the matter further by looking at all opioids, and not just prescription opioids (see below). Prescription opioid overdose deaths are gradually increasing over time. When we include heroin and fentanyl, the more abrupt upward swing for heroin and fentanyl does not take place until the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Looking at death rates (see CDC data below), prescription drugs level off in the 2010s while heroin and fentanyl increase. Why the discrepancy between prescription opioids and the other two?

As the Economist succinctly describes the phenomenon, it is a matter of supply and demand. The prescription overdose deaths make more sense because like other substances or other medical procedures, it does not come risk-free. 2012 was a peak consumption year with 259 million opioid prescriptions filled out. 16,007 people died from prescription opioid use in 2012. Based on those figures, one in 16,180 people die from opioid abuse. Even for those who use opioid prescriptions on a long-term basis, the CDC estimates in a 2016 study that one in 550 die from opioid abuse. Odds of death from opioids are small, but when so many Americans are taking them, the numbers add up. The number of opioid deaths increase because of the growing popularity of prescription opioids.

Increased demand of prescription opioids is only part of the equation. Since prescription opioids were heavily abused in the 2000s, the response of the DEA was production quotas (see DEA data dating back to 2007). Take a look at Florida as an example. In the 2000s, Florida developed a reputation for being America's pill mill capital. In 2010, nine out of ten Oxycontin prescriptions were being written by doctors in Florida. Florida Governor Rick Scott wanted to put a stop to the drug abuse. In 2011, Scott teamed up with the DEA and cracked down on prescription opioid distribution, thereby cutting off a major supply of prescription opioids. The DEA is making the same mistake for the year 2017 by reducing the opioid production quota by 25 percent. The reason I call this a mistake is because when a production quota is enacted (see below), there is not simply an increase of prices. There is also a shortage of the good, which means that the production quota is not fulfilling demand.

When price or income changes (or in this case, both supply and price), then the substitution effect kicks in. In layman's terms, what this means is that if prescription opioids become more expensive or in rarer supply, there is a good chance that the consumer is going to look for another good similar to the oxycontin. This is where heroin and fentanyl enter the scene. I am not here to say that these other opioids didn't exist prior to the U.S.' uptick in prescription opioid production in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The consumption patterns of heroin and fentanyl (see in previous figures above) don't show that it was a clear substitute effect, at least not in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

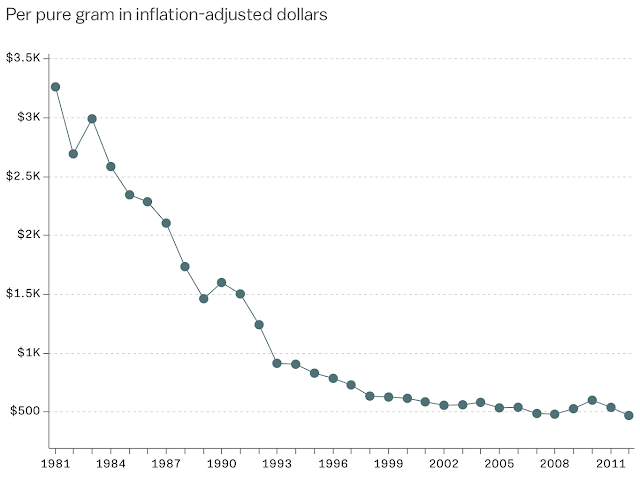

Something else happened to cause an uptick in heroin and fentanyl consumption, aside from heroin getting cheaper (see below). That something else was the Mexican drug cartels. As the Economist points out, the Mexican drug cartels were struggling with selling cocaine and marijuana. In the United States, demand for cocaine had dropped and marijuana had become increasingly legalized. The Mexican drug cartels saw heroin as an opportunity and increased heroin production tenfold in the 2000s.

Why does Mexico's heroin production matter? For one, Trump was actually right when he said that heroin was coming in from the Southern border. In 2012, 45 percent of heroin seized by the DEA came from Mexico. By 2015, that figure increased to 75 percent of seized heroin. This is all the more important because heroin and oxycontin are both opioids. Oxycontin is an FDA-approved, Schedule II drug while heroin is an illicit, Schedule I drug. At the same time, both come from the same poppy plant, both give a similar sense of euphoria, and both have similar pain relief properties. The other main difference is that heroin is more potent. There is very little room for error in dosage, which helps explain the uptick in heroin overdose deaths.

To summarize these economic trends: Since the 1990s, there has been an increased demand for prescription opioids, a potent drug that has 32 percent of prescriptions abused and is prone to addiction much more than alcohol or marijuana. Those who are taking prescription opioids and have developed an addiction are more prone to heroin, particularly when the Mexican drug cartels started its major increase of heroin distribution in the United States during the late 2000s and early 2010s. As a result of flooding the American market with heroin as a substitute good (especially one that is cheaper than prescription opioids), heroin becomes cheaper and more readily available to those already susceptible to heroin. On top of that, the DEA makes the situation worse by limiting the supply of legal prescription opioids, thereby making the illegal ones all the more attractive. What we have is a risky product on the market, and its presence is made all the worse with the Mexican cartel and the DEA's response to prescription opioids. What does the solution involve?

Some might argue that either this is not a big deal or that this is a price of freedom. As I pointed out in a previous paragraph, an estimated one in 16,180 people (0.006 percent) die from opioid abuse, which is 35 times lower than dying of heart disease. That probability goes up to one in 550 (1.8 percent) if it is prolonged opioid use. Even if you're facing prolonged prescription opioid use, is the 1.8 percent risk of dying worth mitigating or eliminating pain in your life? None of this gets into opioid abuse. According to a 2016 study from Castlight Health, 4.5 percent of prescription opioid users are abusers, and account for 32 percent of prescriptions consumed. Plus, heroin users are less likely to be addicted to heroin, but more likely to die from it. Justifying inaction in such a matter is not going to make the problem go away, especially in light of upcoming DEA production quotas that will be even more restrictive. So what can be done?

The Drug Policy Alliance provides a good policy brief (see here), but to summarize, the plan would entail treatment for current opioid abusers and mitigating future opioid abuse. Here is elaboration on some policy alternatives:

- Drug courts versus treatment alternative diversion (TAD). The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) suggests "benign paternalism" in the form of drug courts because recovery is a challenge, especially when considering dropout. Since prescription opioids are legal, this alternative would be more appropriate for heroin users. Wisconsin provides a good example of how a TAD program works (I actually did grad school work on Wisconsin's TAD program). Essentially, instead of dealing with drug courts and a felony a charge, a non-violent drug offender that completes treatment has their records expunged. TAD is a preferable alternative to incarcerating and throwing the book at people who need help.

- Harm Reduction. Harm reduction is a set of policies used to mitigate and lessen the consequences of addiction and substance abuse, particularly for those for whom abstinence does not work. E-cigarettes are an example of harm reduction for those who are dealing with tobacco addiction. Sure, e-cigarettes do not completely eliminate nicotine consumption, but a) it removes other carcinogens, and b) it is healthier than regular cigarettes. Harm reduction examples for opioids include the clean needles exchange, safe injection facilities, bupe, Kraton, and Naloxone. Naloxone is interesting because Naloxone access has reduced opioid deaths by 9 to 11 percent (Rees et al., 2017). Even better, it was found to not increase drug injection, use, or drug-related crime in the area (Potier et al., 2014).

- Marijuana Legalization. Much like heroin has a substitution effect, so does marijuana. Not only does marijuana not deserve a Schedule I label by the DEA, it does not deserve to be criminalized, especially in this context. Those who have allowed for medicinal marijuana have seen a drop in opioid addiction and overdosages (Powell et al., 2015).

- Trump's Border Wall. I covered this topic a few months ago, but essentially, Trump's border wall is not going to impede heroin inflows all that much because as most security analysts point out, smugglers will simply find a way around it.

- Stopping Mexican Drug Cartels. I hesitate with this policy alternative not because I side with the drug cartels. They are peddling a dangerous product into the United States, and it needs to be stopped. The DEA has played a role in making this a worse problem with its production quotas and other regulations, which is why I hesitate in prescribing them as part of the solution. On the other hand, it is not like the Mexican drug cartels will suddenly decide to stop distributing in the United States. Although the "gateway drug" argument is ridiculous when it comes to marijuana, it actually plays out in the context of opioids: prescription opioids often lead to heroin consumption. This gateway gives reason for the cartels to continue distributing their heroin. Unless there is some way market forces can remove Mexican drug cartels in the United States, I have to concede that DEA intervention is the least worst option to stop the cartels. If they are going to go after the drug cartels with full force, they need to lighten up on their prescription opioid production quotas.

- Decrease Criminalization. Similar to the rest of the War on Drugs, criminalization and production quotas exacerbated the situation. Research shows that increased incarceration and punishment for drug-related charges increases overdose rates and does not have a deterrent effect. Additionally, when you restrict supply of prescription opioids and further stigmatize it, users go to the underground market, which leads to users obtaining opioids for which they do not know the dosage or composition, e.g., heroin laced with fentanyl that raises risk of overdose. What this would mean for opioid reform policy is, among other things, not pursuing minimum mandatory sentences, which is the opposite of what Attorney General Jeff Sessions is doing as of last week.

- Effective Treatment Access. According to federal data, 89 percent of those struggling are not getting the treatment they need. While there are multiple reasons, affordability was at the top of the list (see below). There is definitely a market failure for those who want treatment. A market failure does not automatically necessitate a government solution, but the reality is that there will be at least some government intervention.

However, what I can say is this: our policy solutions need to be focused much more on treatment, not criminalization. Although Trump promised to end the opioid crisis, his administration has yet to do anything meaningful about it (although state grants are pending). Whether or not the Trump administration (or any of the state-level governments) carry out some or all of the effective policy options remains to be seen. Let us hope that the Trump administration can prioritize the opioid crisis in a way that actually results in a reduction of opioid overdoses.

1-9-2018 Addendum: The Cato Institute put out an article on how it's less of an opioid crisis and more of a "heroin and fentanyl crisis."

No comments:

Post a Comment