Before delving into the particulars, I want to say that because it is a novel virus (i.e., it has not been previously identified in humans), there will be new information coming in that will better inform us of the severity of coronavirus. That means over time, the situation will evolve. It could either be better or worse than previously predicted. Second, the data used are as of March 12, 2020 at 10:33am EST. Third, I am not an expert epidemiologist, but I will be citing public health experts in the hopes to give you the best information available. Let's begin, shall we?

Reasons to Worry

- A novel disease comes with unknowns. Oftentimes, it is the unknown that scares us more than the known. We don't know if we can cure it. We're not certain about all modes of transmission, although social distancing seems to be one of the best ways to slow down transmission. This affects our sense of risk and control, which can cause anxiety (read this article on how to deal with anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic).

- We do not have a vaccine for COVID-19. People compare COVID-19 to flu season. The flu has a mortality rate of 0.15-0.20 per 100. The problem with that comparison is that there are flu vaccines to keep the mortality rate low. It would most likely take at least 6-12 months to have a vaccine ready for mass production.

- It mimics other viruses. Since its symptoms are non-specific, it is more difficult to determine whether one has COVID-19. Without getting a test, COVID-19 looks quite similar and undistinguishable from a cold or flu. Both the mildness in most cases and issues with detectability make it more difficult to contain.

- Particularly risky for elderly and immunocompromised. The elderly and immunocompromised have a greater difficulty fighting off diseases generally. COVID-19 is particularly bad for these demographics because it can evolve into pneumonia or other major respiratory issues. The fatality rate is estimated at 3.6 percent for those in their sixties, 8 percent for those in their seventies, and 14.8 percent for those in their eighties. To put in perspective, the fatality rate for influenza is 0.83 percent for those in their eighties, but that's because we have a vaccine (see previous point).

- Global macroeconomic risk. If there is anything that markets hate more than regulations, it is uncertainty. It's no wonder that stock markets are taking a nose dive. But it's more than the financial sector that is hit. Especially since China is such a vital contributor to supply chains worldwide, there is a supply shock reverberating across multiple industries. Macroeconomic modeling from the Brookings Institution (McKibbin and Fernando, 2020) has shown that the global economy could easily take a significant hit in the short-run.

- Transmission rate of COVID-19. The basic reproduction number (or R0) indicates the level of transmission of a pathogen. If R0 is less than 1, it means that the pathogen will unlikely pass it on to even one person. A R0 greater than 1 means that one sick person infects one person on average. While still preliminary, a study in the Journal of American Medical Association [JAMA] puts it somewhere between 2.0 and 3.5 (Del Rio and Malani, 2020). This means that someone with coronavirus will, on average, infect at least 2-3 people. Since COVID-19 is so new and certain measures can be enacted (see Postscript at the end), the R0 can change. However, to contextualize the R0, the typical season flu has an R0 of 1.2, SARS has an R0 of about 3.5, smallpox has an R0 of 7, and measles has an R0 between 12 and 18. I put this in "Reasons to Worry" because it is higher than the flu (although again, we now have a vaccine for the flu). At the same time, it is lower than other viruses that have plagued humanity before.

- Another word on transmission: COVID-19 is primarily spread either through person-to-person contact within six feet or respiratory droplets (e.g., coughing sneezing). This helps contribute to its R0. On the other hand, COVID-19 does not seem to be particularly airborne, which is why social distancing works as well as it does (see Postscript).

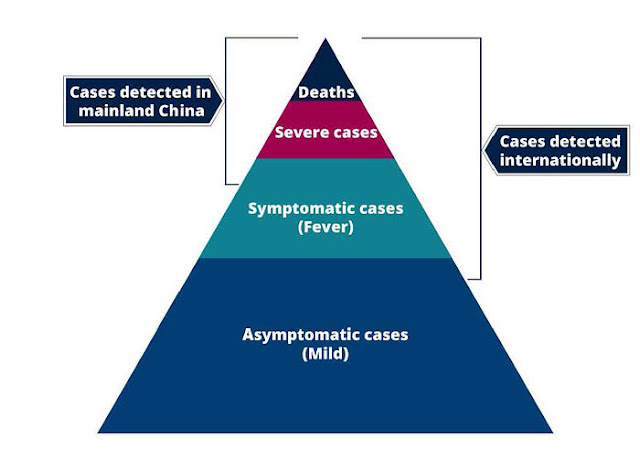

- Possibility of underestimating death toll. If you include all the cases that have not run their course, it is possible that the death rate is underestimated because it does not include cases that could result in death later.

- Potential overload of hospital systems. This is the most valid worry I have seen so far. If the number of those infected with COVID-19 becomes too high too fast, it could overburden the health care system. We already see this playing out in Italy. Overwhelmed health care systems are bad for everyone, not just those infects. This is why epidemiologists suggest social distancing through what is referred to as "flattening the curve." If we can at least prevent COVID-19 from being spread too quickly, it would likely not overburden hospitals.

Reasons to Not Be So Worried

- Most cases of COVID-19 are mild. Coronavirus is not a death sentence for the vast majority of those infected. Eighty percent of those infected have such minor symptoms and do not require care, according to Dr. Robert Murphy, who is the Executive Director of the Institute of Global Health at Northwestern University. A study of over 72,000 Chinese individuals who had COVID-19 concludes that 81 percent of those infected have a mild form of COVID-19 (Wu and McGoogan, 2020). As the WHO stated, "most people will have a mild disease and get better without needing any special care."

- Estimated mortality rate likely to be too high. Yes, the WHO estimates that 3-4 percent of COVID-19 cases have died. The caveat here is "reported" cases. Since there are more hard-to-count cases (see previous point), it is reasonable to assume that the current estimated mortality rate of 3.0 deaths per 1,000 is too high.

- Another reason for optimism: South Korea has tested 140,000 people. There have been 6,000 confirmed cases with a mortality rate of 0.6 people. This is not only significant because they have an ample sample size, but also because South Korea has brought done the infection rate without resorting to citywide lockdowns seen in China and Italy.

- A report from the New England Journal of Medicine (Fauci et al., 2020) points out that pneumonia has a mortality rate of 2 percent, which is worth pointing out since some coronavirus cases lead to pneumonia. Assuming that the number of mild or asymptomatic cases is much higher, the report predicts that the mortality rate will be much closer to flu season [of 0.15 percent], as opposed to a SARS-like 9-10 percent.

- A preliminary modeling analysis from European researchers shows that the mortality rate can be as low as 0.15 per 100 people (Anastassopoulu et al., 2020), which would make it comparable to the flu.

- Progress has already been made. While there is still not a vaccine, we already have a head-start in comparison to past epidemics. First, we have already identified the genome. Contrast that to HIV/AIDS, which took two years to identify. Second, we have been able to detect the virus since January 13 (Corman et al., 2020). We already have 164 scientific articles on COVID-19 that are accessible. For the SARS epidemic of 2003, it took a year to reach half of that amount. Finally, there are already vaccine prototypes and there are 80 clinical trials that have been launched.

- Many more recoveries than deaths. There have been 68,310 recoveries while there have been 4,718 deaths. That means that for every death, there have been over 14 recoveries (Johns Hopkins).

- Lower death rate for younger people. With the data from China, the death rate for those under 40 is 0.2 per 100, and 0.4 for those between 40 and 50 (Wu and McGoogan, 2020).

- Number of cases in already-affected countries is leveling off. This point is brought up by economist Anatole Kaletsky. Because it is an exponential process, Kaletsky uses a logarithmic scale. With that scale, Kaletsky shows how the spread of COVID-19 in the countries affected earliest in the outbreak are leveling off (see below). This finding can also suggest that the contagion effect is weaker than initially anticipated.

The first person fell ill to COVID-19 about three months ago. For many countries, including my home country of the United States, we are in the outbreak stage of coronavirus, which means that any findings are preliminary. What we do know seems to provide a sense of mixed blessing, although I would say that the media has overblown COVID-19 based on information we have so far and that there is reason for medium-term optimism. Yes, there is risk, as there is for any pandemic. While we should not dismiss areas of concern, COVID-19 needs to be kept in perspective.

COVID-19 is especially a problem if you are elderly or are immunocompromised. However, for most people infected, the effects of coronavirus will be minimal or simply nonexistent. That's on an individual level. The implications for public health and the economy depend on how well we can slow the spread of coronavirus. It is too soon to tell what the magnitude of the effects of coronavirus will be, but it is safe to say that it will get worse before it gets better. In the meantime, the best ways to minimize contagion are to wash your hands, minimize social interactions, avoid close contact, clean surfaces you use often, work remotely if you can, and only wear a face mask if you are sick (or if you are caring for someone who is sick). Let's hope that we can do enough to minimize the spread of coronavirus and make the coronavirus scare as much of a thing of the past as we did with SARS and H1N1.

No comments:

Post a Comment