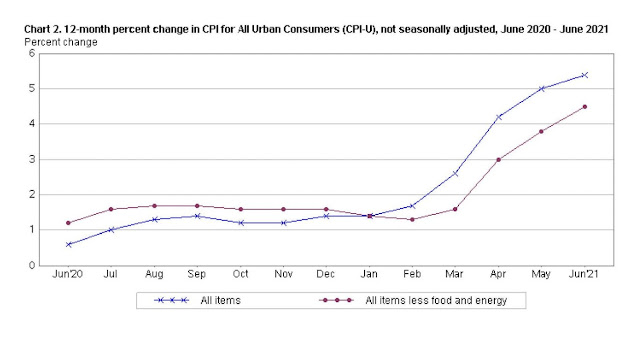

The cost of gasoline has jumped quite a bit. Lumber prices are spiking. Prices for meat, riding share services, semiconductors, and many other goods and services are seeing quite the increase. There is a bit of scare on the media about the rising inflation (see Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI data below), something that could perhaps be worse than what the United States experience in the 1970s. Before beginning, let us ask what exactly is inflation.

As the Peter G. Peterson Foundation states in its primer on inflation, inflation is "the rate at which prices for goods and services increase across an economy." There are two main types of inflation: cost-pull inflation and demand-pull inflation. Cost-pull inflation occurs when prices in production costs increase. A good example of cost-pull inflation is the oil shocks of the 1970s both because they are major production inputs and because of its impact. Demand-pull inflation is when there is a wide consumer demand for goods and services across the economy results in increased prices.

A moderate amount of inflation is considered by many economists to be healthy. Why? Because economic growth comes through an increase in demand of goods and services. With an increase in demand comes an increase in prices. Now, if inflation is too low (or even goes into deflation territory), it means that the economy is not doing well and that wages get depressed. If inflation increases too much too quickly, purchasing power gets eroded. It is a reason why such banks as the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank and the Bank of England have the goal of keeping inflation at a long-term average of 2 percent.

On the other hand, I have to wonder if even if modest inflation is a good goal. When I analyzed the gold standard back in 2013, I found that long-term inflation was more stable under the gold standard. Plus, the understanding of the Federal Reserve's goal of inflation at 2 percent is based on the flawed Phillips Curve. As this publication from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank shows, there is a strong case to be made for price stability, i.e., inflation at or near zero.

We can get into the pluses and minuses of various measurements of inflation, as whether it makes more sense to look on a market-by-market basis (e.g., macroeconomic) versus such a high-level. But let's assume that inflation is one form of adequate measure of economic health. What about the inflation now? What has been driving the inflation since the beginning of the pandemic? Here are a few possibilities being posited by analysts and pundits:

- Energy Prices: With the lockdowns, demand for gasoline dropped considerably, which caused oil prices to decline. Generally speaking, energy prices tend to fluctuate and can easily be reversed. In spite of gasoline prices fluctuating over the past few decades, we have not had massive levels of inflation. Plus, as the Cato Institute points out, when you look at the Consumer Price Index less energy, the fluctuations are not nearly as scary.

- Used Cars: During the pandemic, car-rental companies sold parts of their fleet due to the decline in demand. The demand picked up as the pandemic improved. There is a bottleneck due to the sudden fluctuation in a demand, a fluctuation that should be temporary.

- Unemployment Benefits and Stimulus Payments: I have criticized unemployment benefits and stimulus payments before, but I think this is another potential issue with these policies vis-à-vis inflation. As the Heritage Foundation brings up in its analysis on the latest inflation, households have an unusually high amount of disposable income. That increase is, in no small part, due to the unemployment benefits. While it could be the case that we reach a point of "too many dollars chasing too few goods," the fact that savings rates are higher than normal mitigate that concern. It largely depends on how spending patterns unfold as the economy recovers.

- As an additional note, the continued unemployment benefits give additional incentive to stay at home. This, in turn, creates labor shortages. The labor shortages help assure that supply cannot keep up with demand.

- Quantitative Easing. I thought the quantitative easing during the Great Recession was a large amount. The Federal Reserve has printed money (see M2 money supply) at an unprecedented rate. There is concern that a huge, sudden influx of money injected into the economy. However, as the Heritage Foundation points out, the correlation between M2 and inflation is quite minimal. If anything, there have historically been moments of low inflation even after increases of M2. In the case of this pandemic, inflation was not as bad because the velocity (i.e., the rate at which money is spent) was much lower during the pandemic when people were in lockdowns and businesses were closed. At least in the short-run, we did not see inflation run rampant due to lower velocity. My concern, however, is that as the economy recovers and more money moves through the economy, it will most likely push up prices.

No comments:

Post a Comment